Abstract

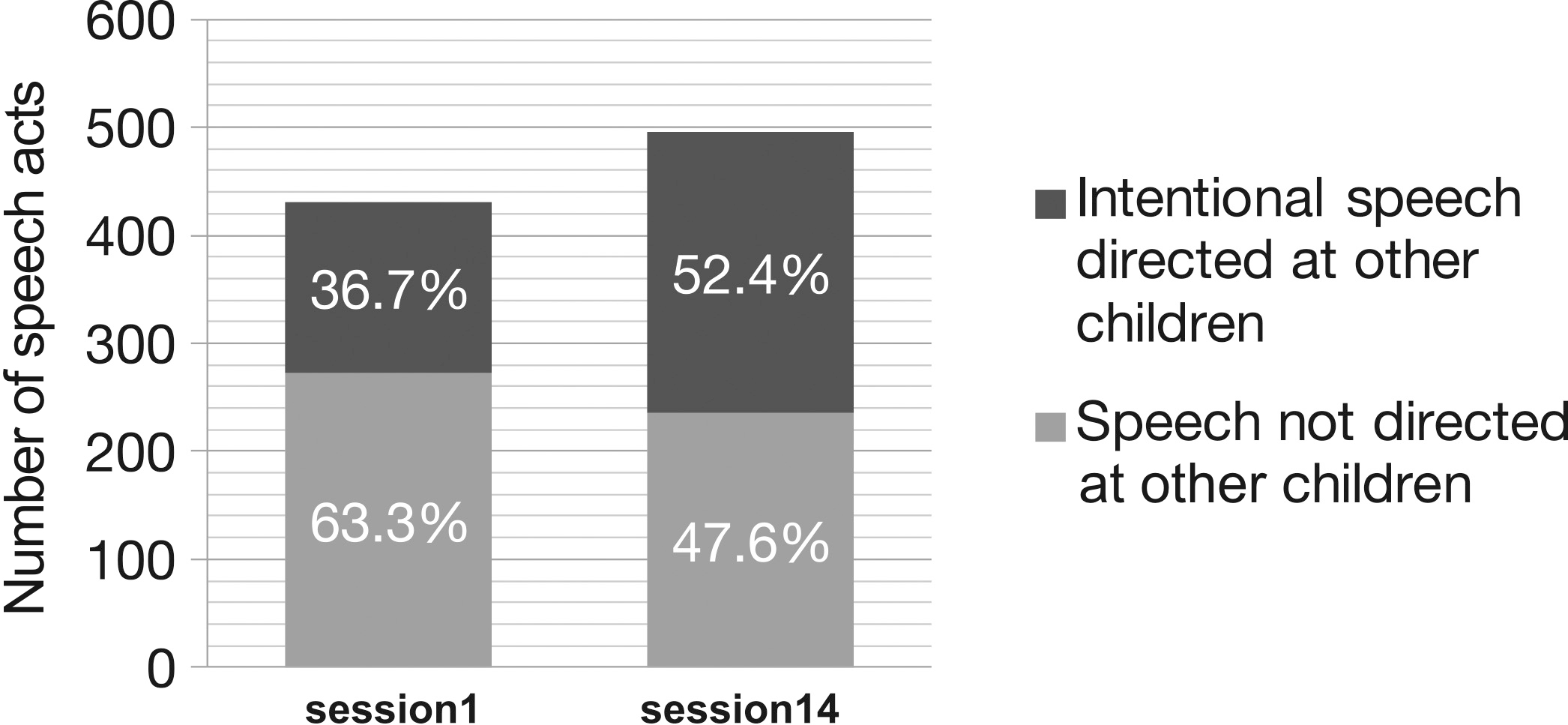

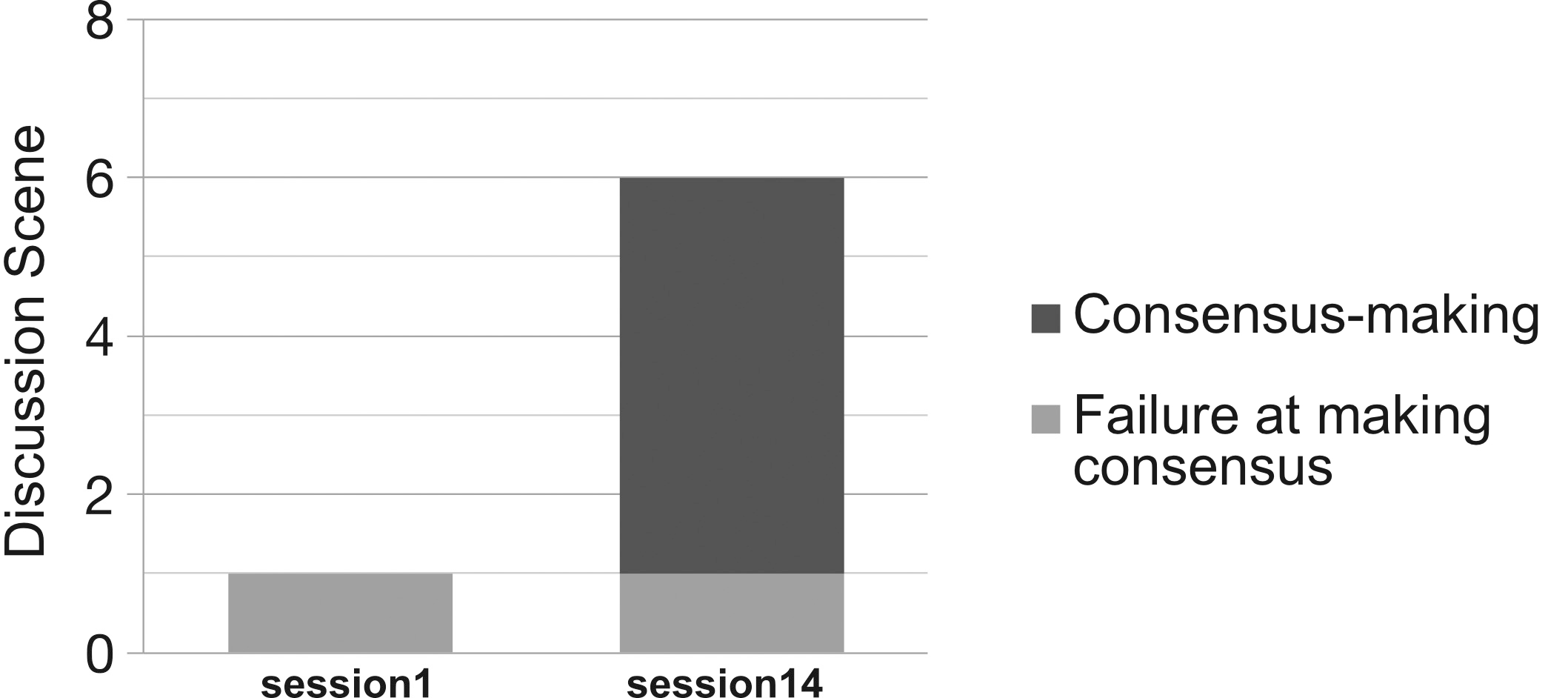

[0.1] This paper presents two studies on promoting social communication and leisure satisfaction of children and youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) through the use of tabletop role-playing games (TRPGs). The first study involved four junior high school students with ASD, and focused on “intentional speech directed to other children” and their “consensu-making” during TRPG play sessions. The results of the analysis suggest that intentional speech as well as the ability to reach consensus increased remarkably between the 14th and the 1st session.

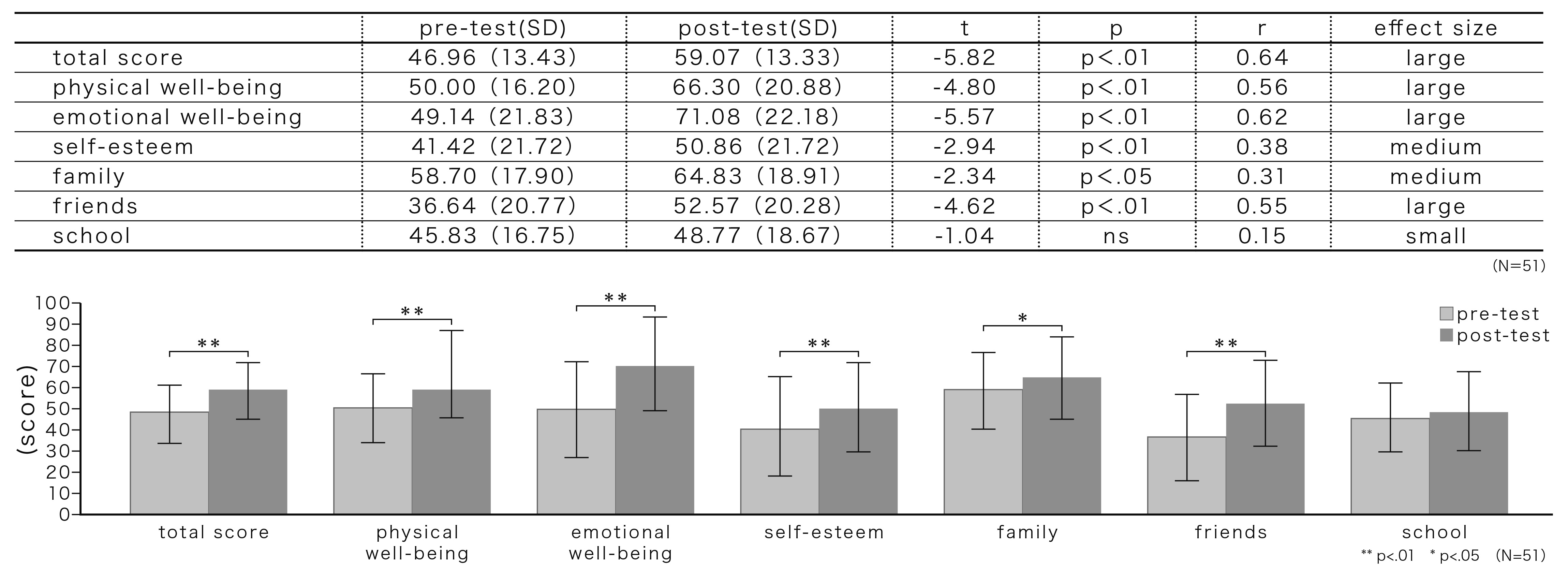

[0.2] The second study investigated the efficacy of leisure activity using TRPGs to enhance the quality of life (QOL) of children and youth with ASD. Fifty-five teenagers with high-functioning ASD participated in the study and responded to the standardized “Questionnaire for Measuring Quality of Life” before and after the TRPG activities. After a total of five sessions once a month significant improvement in the total scores and most of subscales of QOL could be observed. The subscales of “emotional well-being” and “friends” in particular, improved remarkably. These findings suggest that leisure activities using TRPGs have the potential to promote social communication and enhance QOL in children and youth with ASD.

[0.3] Keywords: Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), tabletop role-playing games (TRPGs), communication support, leisure activity support, quality of life (QOL)

要約

[0.4] 本研究では,TRPG活動を通じた自閉スペクトラム症のある子ども・若者(ASD児者)自身の社会的コミュニケーション支援の効果およびTRPG活動の余暇活動としての満足度とその意義と可能性について検討することを目的とした.第1研究では,ASD児4名を対象にTRPGを実施し,初期の活動と最後の時期の活動での会話内容を比較した.その結果TRPG場面でASD児たちの自発的な発話が有意に促進されていることとTRPG中の話し合い場面での合意形成の数に明らかな増加がありポジティブな変化が見られたことが明らかになった.

[0.5] また第2研究では,TRPG活動に参加したASD児者51名を対象にTRPG活動実施の前後にQOL尺度への回答を求めた.その結果,QOL総得点およびすべての下位因子で得点が伸び,TRPGがASD児者にとって満足度の高い余暇活動で,QOL向上にも影響があることが明らかになった.また,ASD児者10名に面接調査を行ったところ,彼らがTRPG活動に満足しており,TRPGを通じた自身のコミュニケーションの変化を自覚していることも明らかになった.TRPG活動はASD児にとって満足度の高い活動であり,活動を通じて彼らの社会的コミュニケーション促進する可能性が示唆された.

[0.6] キーワード:自閉スペクトラム症 (ASD), テーブルトーク・ロールプレイングゲーム (TRPG), コミュニケーション支援, 余暇活動支援, 生活の質 (QOL)

日本語読者への注

[0.7] 本稿について日本語で概要を知るには,加藤ら(2012),加藤ら(2013),加藤ら(2016)を参照のこと.

1. Introduction

[1.1] Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by qualitative impairments in social interaction and communication, as well as restricted, repetitive behaviors, activities, and/or interests (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Among these characteristics, difficulties with social communication are often described as a core deficit of ASD (White, Keonig, and Scahill 2007).

[1.2] ASD is a congenital disorder with symptoms presenting from early childhood and affecting daily life functions. However, ASD is often misunderstood as a lack of effort of the afflicted or as a mental sickness of the child caused by the mother when the child grew up.

[1.3] Currently, special education for children with ASD, ADHD (Attention-Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder), and SLD (Specific Learning Disorder) is one of the major topics at school sites in Japan. Much attention focuses on how children with ASD have difficulties with social communication and participating in group activities with people of the same age. Without support, children and youth with ASD may suffer from the following difficulties, among others (1) Initiating, maintaining and developing a conversation, (2) inviting classmates over to play, (3) joining group activities (4) keeping up with a game or understanding its rules (Bailey 2007). Improving social communication skills of children with ASD is a challenge of vast importance in contemporary education.

[1.4] So-called social skills training (SST) ranks high among measures employed to support social communication of children with ASD. SST is a specific intervention that intends to help children and adults improve their social skills so they can increase their social competence. This intervention involves teaching specific communication skills through behavioral and social learning techniques. SST has been used as an intervention approach for children and youth with ASD since the 1980s (Mesibov 1984). SST support for children with ASD includes various approaches for individual but also small group support (Bauminger 2002; Tse et al. 2007; Frankel et al. 2010).

[1.5] However, Rao, Beidel & Murray (2008) suggest that there are few studies about SST programs for children and youth with ASD that indicate generalizable therapeutic effects. In addition, Koenig, De Los Reyes, Cicchetti, Scahill & Klin (2009) show that interpersonal interactions are multi-dimensional and complex, so social communication support for children with ASD should be comprehensive and tailored to individual needs. Consequently, the authors suggest a necessity to develop alternative programs that encourage learning of social communication for ASD (2008). In addition, it is difficult for ASD children to use their conversation skills on a daily basis simply by providing training-based communication support that teaches routine methods. Therefore, it is important to foster motivation to communicate with children with ASD.

[1.6] Meanwhile, taking a slightly more play-minded perspective with less a focus on strict training, support for social communication of children and youth with ASD based on leisure or hobby activities has attracted attention in recent years. Oi (2005) posits that experience with small group activities where all participants show the same disorder characteristics are vital for the growth of social communication skills of children with ASD. Many studies of support measures for individuals with ASD based on leisure activities focus on group participation, stress coping, and quality of life (QOL). García-Villamisar & Dattilo (2010) suggest that participation in recreational activities positively influences the stress, QOL, and social interactions of adults with ASD. Furthermore, several studies conducted in Japan practice report about social interaction support through leisure activities that include hobbies and interests of young people with ASD. Nitto, Yurugi, Takebe & Honda (2011) reported based on follow-ups that 56% of children’s friendships were maintained as a result of implementing a common hobby-based friendship program for children with ASD. Kato, Iwaoka & Fujino (2019) suggest that leisure activity support for children and youth with ASD using “hobby talk activities” can be effective to promote interaction among participants depending on the method of conversation analysis.

[1.7] Kato, Fujino, Itoi & Yoneda (2012) demonstrated the importance of approaches and environment designs focusing on the children’s spontaneity and interests. In order to achieve this, we adopted the leisure activity tabletop role-playing games (TRPGs) as programs to fit these conditions. TRPGs are interactive games in which a small group of players creates a fictional story using only pencils, paper, dice, and conversation. Players determine the actions of their characters based on their personalities, backgrounds and through role-playing. These actions succeed or fail according to a formal system of rules and guidelines (Figure 1, Figure 2).

Fig. 1: A group playing TRPGs.

Fig. 2: Tools used to play TRPGs (rulebook, character sheet, pencil, dice).

[1.8] TRPGs are utilized in education and development support. Karwowski & Soszynski (2008) described how role-playing training increased the creative thinking ability of college students. Chung (2013) reported that a group of TRPG players had a higher divergent thinking value than groups not playing as a result of a creativity test for adults who are playing TRPG and who are not playing. His results suggested that TRPG may promote the creativity of their players. Rosselet & Stauffer (2013) detail a therapeutic approach using TRPGs to train social and emotional self-regulation skills in gifted children and adolescents. Robinson introduces TRPG research and practices on the web from the perspective of recreational therapy for children and adults with disabilities and handicaps (http://rpgresearch.com). The Game to Grow therapeutic social skills groups primarily use TRPGs to help teens build tangible social skills (https://gametogrow.org).

[1.9] Over the past decade, I have been engaged in TRPG leisure activities for children, adolescents and adults with ASD for research and support purposes [Katō et al. (2012); Katō, Fujino, and Yoneda (2013); Katō and Fujino (2016); https://sunpro8.wixsite.com/sunpro]. This paper presents the results of promoting social communication and leisure satisfaction of children and youth with ASD through TRPGs.

3. Second study: Do activities involving tabletop role-playing games enhance the quality of life in children with autism spectrum disorder?

[3.1] (1) Purpose – We focused on small-group activities involving TRPGs as a method for promoting social interaction among children with ASD. Previous studies have shown that leisure activities such as TRPG promote intentional communication and cooperative interaction among children with ASD. This study investigated the efficacy of TRPG activities to enhance QOL in children with ASD.

[3.2] (2) Methods – The participants were 51 teenage children (forty-one male and ten female) with ASD (average chronological age: 14, average FIQ score: 101). We used the Japanese version of the Kid-KINDL Questionnaire in this study.3 The participants answered the questionnaire before and after participation in five sessions of activities involving TRPGs. The amount of change in the scores before and after the intervention period was statistically compared using a t-test.4 In addition, interview surveys were conducted with ten children (seven male and three female) with ASD (average chronological age: 14.9, average FIQ score: 112.5) to hear their impressions about TRPGs.

[3.3] (3) Results – There was a significant improvement in the total scores of QOL. The effect size (r) of the subscales in each outcome measure were as follows: ‘physical well-being’ 0.56 (large); ‘emotional well-being’ 0.62 (large); ‘self-esteem’ 0.38 (medium); ‘family’ 0.31 (medium); ‘friends’ 0.55 (large) and ‘school’ 0.15 (small), see figure 5.

Fig. 5: Mean scores on the subscales in QOL.

[3.4] Then, in an interview survey of children with ASD, there were comments such as “After experiencing TRPG, I have enjoyed talking more than before” and “I think TRPGs have more options for what we can do than in everyday life.” amongst others (Table 1).

| Table 1: Comments from children with ASD (partial excerpts) |

|---|

・The role of my character was different from myself in real life. However, I was satisfied with the thought that “I can only do this role.” (15, male) ・When I was in a character crisis during sessions, other characters helped me. Even if one of the parties failed, other members supported him in TRPGs. (15, male) ・TRPGs are continuous laughing activities. Interaction between players, other players and GM creates laughter. (15, male) ・I think TRPGs have more options for what we can do than in everyday life. (14, male) ・TRPGs have a high degree of freedom. It’s great that we can try through our character what we want to do in role play. (14, male) ・Even if my character’s action failed, I enjoyed the action as one of the story events. (15, male) ・Apart from the fun of TRPG, I enjoyed communicating with other players. (14, female) ・I feel that the relationship between TRPG players and characters is not “equal” or “not equal” but “nearly equal.” (15, male) ・After a session, we were able to chat about the events and role-playing in the scenario. That experience enabled me to be able to speak naturally. (18, male) ・After experiencing TRPGs I have enjoyed talking more than before. (17, female) ・I enjoyed the sensation of thinking during the adventure, that “at first glance, we may not be companions, but actually we are.” (13, female) ・Unlike computer games, TRPGs allow for fun talking because real participants are there. (15, male) |

| (phrases in brackets show age and gender of interviewees) |

[3.5] (4) Conclusion – These results suggest that leisure activities involving TRPGs have the potential to enhance QOL (particularly, ‘emotional well-being’ and ‘friends’) and relationships with peers of teenagers with ASD. Furthermore, it was suggested through interviews that children and youth with ASD are learning appropriate strategies and skills for social communication and interpersonal relationships while enjoying TRPGs. Additionally, they were aware of positive changes in their own communication skills through TRPGs.

4. Summary

[4.1] Currently, the limitations of training-type communication support for ASD represented by SSTs become apparent. Subsequently, support for interpersonal relationships and social communication through leisure activities garners attention.

[4.2] Leisure and hobby activities are the basis for forming friendships among children and youth with ASD and promote their communication proficiency. However, simple conversation about a hobby rather feeds into disability characteristics of ASD, such as one-way communication, narrow range of interests, etc. (Shimizu 2004; Ōi 2005).

[4.3] TRPGs function differently than colloquial talks. From our research and practice so far, we hypothesized that TRPGs contain elements that promote interpersonal relationships and social communication among children and youth with ASD: (1) rules and settings as a framework of the activities, (2) clarification of common goals and roles, (3) indirect communication through a character (Katō et al. 2012).

[4.4] The results of previous and our current research have shown that TRPGs promote communication (intentional speech and consensus making) and increases scores of QOL for children and youth with ASD. In addition, we were able to obtain answers that supported our hypotheses in the interview survey of the second study.

[4.5] There are many misunderstandings concerning ASD, and those who suffer from the disorder and their families are often the victims of stereotyping and biases. For example, it is generally said that “children and youth with ASD are not good at communication,” “individuals with ASD hate group activities.” However, they are not necessarily poor at group activities and social communications.

[4.6] If the form of environment and support matches a child, they enjoy spontaneous conversation and interaction, and freely demonstrate their unique and prosperous creativity. I am convinced of the effectiveness of leisure activities for children with ASD involving TRPGs, that we conducted as part of my research.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on a major revision of a presentation delivered at the TRPG Festival 2018 (August 31-September 2, 2018, Atami City).

Notes

A full intelligence quotient (FIQ) is a total score derived from several standardized tests designed to assess human intelligence.↩︎

Statistical test method used for the analysis of data classified into two categories.↩︎

Self-assessment questionnaire measuring the quality of life (QOL) of children and adolescents.↩︎

Statistical test method used to assess, whether the means of two groups are statistically different from each other.↩︎

References

Akita, Kiyomi. 2000. Kodomo wo hagukumu jugyō-zukuri - chi no sōzō he [Creating Classes to Nurture Children: The Creation of Knowledge]. Tokyo: Iwanami.

American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition: DSM-5. 5 edition. Washington, D.C: APP.

Attwood, Tony. 2008. The Complete Guide to Asperger’s Syndrome. London: JKP.

Bailey, Megan. 2007. Social Skill Intervention Strategies for Children with Autism. Presented at SAARC. https://www.cigna.com/assets/docs/behavioral-health-series/autism/2012/socialSkills.pdf (accessed 2019/8/31).

Bauminger, Nirit. 2002. The Facilitation of Social-Emotional Understanding and Social Interaction in High-Functioning Children with Autism: Intervention Outcomes. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 32 (4): 283–298. doi:10.1023/A:1016378718278.

Bishop, Dorothy V., and Catherine Adams. 1989. Conversational characteristics of children with semantic-pragmatic disorder. II: What features lead to a judgement of inappropriacy? The British Journal of Disorders of Communication 24 (3): 241–263.

Chung, Tsui-shan. 2013. Table-top role playing game and creativity. Thinking Skills and Creativity 8 (April): 56–71. doi:10.1016/j.tsc.2012.06.002.

Frankel, Fred, Robert Myatt, Catherine Sugar, Cynthia Whitham, Clarissa M. Gorospe, Elizabeth Laugeson, F. Frankel, C. M. Gorospe, and E. Laugeson. 2010. A randomized controlled study of parent-assisted children’s friendship training with children having autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 827–842.

García-Villamisar, Domingo A., and James Dattilo. 2010. Effects of a leisure programme on quality of life and stress of individuals with ASD: Effects of a leisure programme. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 54 (7): 611–619. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01289.x.

Karwowski, Maciej, and Marcin Soszynski. 2008. How to develop creative imagination?: Assumptions, aims and effectiveness of Role Play Training in Creativity (RPTC). Thinking Skills and Creativity 3 (2): 163–171. doi:10.1016/j.tsc.2008.07.001.

Katō, Kōhei, and Hiroshi Fujino. 2016. TRPG ha ASD no ko no QOL wo takameru ka? [Do TRPG activities enhance QOL in Children with ASD?]. Bulletin of Tokyo Gakugei University Educational sciences, 67 (2): 215–221.

Katō, Kōhei, Hiroshi Fujino, Takeshi Itoi, and Shūsuke Yoneda. 2012. Kōinōjiheshõ supekutoramu ko no shōshūan ni okeru komyunikēshon-shien: Tēburu tōku rōrupureingu gēmu (TRPG) no yūkōsei nitsuite [Communication Support for Small Groups of Children with High Function Autism Spectrum Disorder: Effectiveness of a Table-talk Role Playing Game (TRPG)]. The Japanese Journal of Communication Disorders 29 (1): 9–17.

Katō, Kōhei, Hiroshi Fujino, and Shusuke Yoneda. 2013. Tēburutōku rōrupureingu gēmu katsudō ni okeru kōkinōjiheishō supekutoramu-ko no gōikeiseikatei [A Process of ‘Consensus Making’ in Small Groups of Children with High Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder, Using a Table-Talk Role-Playing Game]. The Japanese Journal of Communication Disorders 30 (3): 147–154.

Katō, Kōhei, Tomoki Iwaoka, and Hiroshi Fujino. 2019. Jihei-supekutoramu-shō ko no kaiwa no tokuchō to wadai to no kanren: anime, manga, gēmu wo daizai ni sita ‘shumi tōku’ no jissen [Relationship between topic and feature of conversations of children with autism spectrum disorder: Hobby talk activities with topics about animation, manga, and games]. Bulletin of Tokyo Gakugei University Educational sciences, 70 (1): 489–497.

Koenig, Kathleen, Andres De Los Reyes, Domenic Cicchetti, Lawrence Scahill, and Ami Klin. 2009. Group Intervention to Promote Social Skills in School-age Children with Pervasive Developmental Disorders: Reconsidering Efficacy. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 39 (8): 1163–1172. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0728-1.

Mesibov, Gary B. 1984. Social skills training with verbal autistic adolescents and adults: A program model. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 14 (4): 395. doi:10.1007/BF02409830.

Nitto, Yukari, Haruka Yurugi, Masaaki Takebe, and et al. 2011. Asuperugā shōkōgun no gakurei-ji ni taisuru shakai sanka shien no atarashī hōryaku – kyōtsū no kyōmi o baikai to shita hon’nin dōshi no nakama kankei keisei to oya no sapōto taisei-dzukuri [A new strategy to promote social participation for school-age children with Asperger’s syndrome: helping children develop friendship via their hobbies and interests in common and parents build support networks]. Clinical Psychiatry (Japan) 52 (11): 1049–1056.

Ōi, Manabu. 2005. Seinen-ki no gurūpu katsudō ga motsu imi [Meaning of group activities in adolescence]. In Asuperugā shōkōgun to kōkinōjiheishō [Asperger Syndrome and High Functioning Autism], edited by Toshirō Sugiyama. Tokyo: Gakken.

Rao, Patricia, Deborah Beidel, and Michael Murray. 2008. Social Skills Interventions for Children with Asperger’s Syndrome or High-Functioning Autism: A Review and Recommendations. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 38 (March): 353–61. doi:10.1007/s10803-007-0402-4.

Rosselet, Julien G., and Sarah D. Stauffer. 2013. Using group role-playing games with gifted children and adolescents: A psychosocial intervention model. International Journal of Play Therapy 22 (4): 173–192. doi:10.1037/a0034557.

Shimizu, Satoshi. 2004. Kōkinōjiheishō-ji he no gurūpu apurōchi [Group approach to high-functioning autistic children]. Asupe-Hāto 6: 10–15.

Tse, Jeanie, Jack Strulovitch, Vicki Tagalakis, Linyan Meng, and Eric Fombonne. 2007. Social Skills Training for Adolescents with Asperger Syndrome and High-Functioning Autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 37 (10): 1960–1968. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0343-3.

White, Susan Williams, Kathleen Keonig, and Lawrence Scahill. 2007. Social Skills Development in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Review of the Intervention Research. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 37 (10): 1858–1868. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0320-x.

Wing, Lorna. 2003. The Autistic Spectrum : A Guide for Parents and Professionals. 2nd edition. London: Robinson.